Ashleigh Jones / Contributing Writer

Amidst soothing, space-like music, stars and galaxies projected on the planetarium dome floated by to the voices of Professor Don Olive and planetarium intern Caroline Hood as each explained the significant contributions women have made in astronomy.

“The Hidden Figures of Astronomy,” a free show hosted by the Christenberry Planetarium on March 25 and 26, aimed to highlight some of the women that have been very influential in the field.

“For women’s history month, we just thought that we would highlight some of the really cool women in astronomy,” said Adaline Pace, one of the planetarium interns who helped prepare social media and posters for this event.

This show focused on the multiple influential women, one of whom was named Henrietta Leavitt. Leavitt was an influential astronomer who provided the foundation for astronomers such as Edwin Hubble to make his monumental discovery that the universe is expanding.

“It was Henrietta Leavitt’s work that Edwin Hubble used to make all of his great discoveries,” Physics Chair and Professor Don Olive said. “And so he gets this credit, but it was really the techniques, and the mechanisms, and the tools that Henrietta Leavitt had developed about 10 years before.”

Born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, in 1868, Leavitt did not receive any formal astronomy training until taking a class her senior year at Radcliffe College, Harvard’s school for girls. Shortly after graduation though, tragedy struck. She developed health complications during a trip to Europe and became deaf at just 21 years old. Despite this, however, she still pursued active involvement at Harvard’s Observatory as a volunteer.

Soon after volunteering, the observatory director, Charles Pickering, noticed her skill for math and attention to detail and promoted her to the job title of “computer.” A computer was a person who analyzed astronomical pictures on photographic glass plates, made calculations, and interpreted data. This was before the arrival of modern computers, which would come decades later.

It was in doing this computing work that Leavitt helped make discoveries that equipped scientists to be able to measure how far away stars are in relation to our Milky Way Galaxy, which is significant because at that time there was no clarity about whether the universe was composed of one giant galaxy or if other galaxies existed outside of the Milky Way.

Leavitt studied the brightness of stars in the large and small Magellanic Cloud galaxies (named after Magellan). These stars are called Cepheid variable stars and their brightness fluctuates back and forth over a certain amount of days. She noticed that some stars would become bright very quickly, and then take a while to become dim. The cycles that these stars undergo from brightness to dimness and back to brightness is called a period. Some stars took long periods, while other ones had short ones.

“She noticed that there is a simple relationship between the brightness of the variable and their periods,” Olive said.

In short, her discovery allowed scientists to be able to measure the distance of stars. This became very important when Edwin Hubble studied the Andromeda galaxy, which we now know is the closest galaxy to the Milky Way. He calculated that the Andromeda galaxy was 2.5 million light years across using Leavitt’s previous methods. The Milky Way, by comparison, was only 100,000 light years across. This meant that the Andromeda galaxy was outside the Milky Way, a completely different galaxy which meant the universe was not confined to just one galaxy.

“This discovery ignited everyone’s imagination,” Olive said. “It radically changed our understanding of the size, the nature, and the makeup of the universe. It changed everything.”

Hubble’s discovery would not have been possible without Henrietta Leavitt. Nevertheless, she was only paid 30 cents an hour for her job and her net worth at death was only $134.

Other influential women in astronomy also faced obstacles. Vera Rubin, who meticulously studied galaxy rotation and disproved that galaxies rotate around a pole, was unable to present her research findings at an American Astronomical Society conference because she was visibly pregnant.

“She was even turned down from Princeton,” Hood said during the presentation.

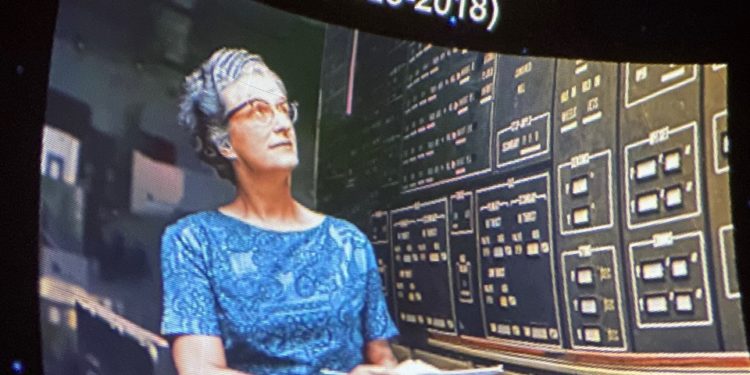

Additionally, Nancy Grace Roman, the first woman to hold an executive position at NASA, experienced rejection during graduate school when one of her professors chose not to speak to her for six months.

According to Hood during the presentation, Roman is often referred to as the “Mother of Hubble” for her influential work in proposing the creation and launch of the Hubble Space Telescope.

“We accredit her for the expansive research and knowledge that we have today of space through this Hubble telescope” Hood said.

This presentation helped spread awareness of the amazing women who have helped shape the field of astronomy. Pace talked about how these women’s stories are admirable in that they succeeded in the midst of adversity.

“Just how they have been able to overcome that and be so successful — it’s just an inspiration to anybody who’s interested in this,” she said.

To stay tuned for future events, students can follow the planetarium’s instagram @samfordplanetarium.