By Ashleigh Jones

On Monday, Sept. 26, students and other interested viewers gathered in Brock Forum to hear visiting poet Nickole Brown speak as the first writer of this year’s Bache Visiting Writers Series.

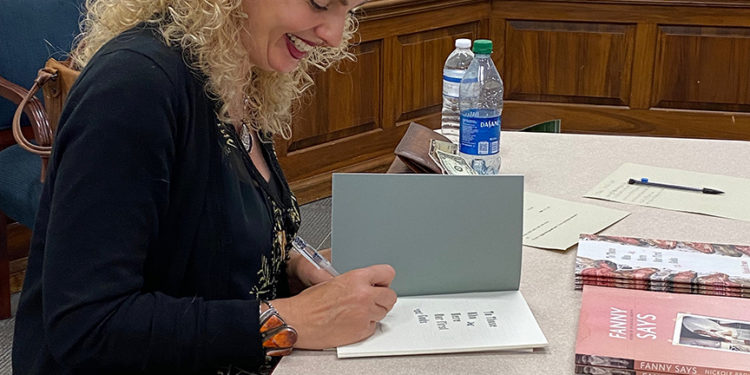

During the event, Brown read several of her poems, answered multiple questions from the audience and stayed afterwards for a book signing.

Her first book, Sister (2007), is an epistolary novel-in-poems, and Fanny Says (2015), her second collection, is a biography-in-poems about her grandmother. Brown’s most recent books, To Those Who Were Our First Gods (2018), and The Donkey Elegies (2020), both examine human’s relationship with animals and highlight the beauty and worth of creatures often ignored.

“I have always loved animals,” Brown said.

The Kentucky native, however, was not allowed to have pets growing up. Despite this, Brown never lost her interest in animals and considered following this passion later on when she and her wife relocated to Asheville, N.C.

“I was trying to redefine my life sort of on my own terms and the one thing that I had always regretted was that I never studied zoology,” she said.

Due to her interest, Brown ordered many books on various animals and started reading them intently. Eventually, she started volunteering at local animal sanctuaries in Asheville.

“I volunteer at a farm sanctuary and I do some wildlife rehabilitation work and I work with horses and donkeys,” Brown said.

Although she has had to perform less glamorous tasks (such as shoveling animal poop), she still finds satisfaction in interacting with animals.

“I absolutely love being around them,” Brown said. “They’ve taught me so much about being in my body, about creation.”

Brown’s experience working in animal sanctuaries has helped provide inspiration for her poems. One of the poems she read for the event, “A Prayer to Talk to Animals,” bemoans the tendency humans have to be constantly glued to our screens, oblivious to all that is happening around us.

Brown has been able to observe the animals one-on-one. She encourages others who visit the barn to meet the animals and enjoy the peaceful stillness of observing rather than chatting with other visitors the whole time.

“It is a quiet that makes most people very uncomfortable, and it did for me for a long time until I really began to love it,” she said.

Another poem, called “Prayer to be Still and Know” came about after a walk with her golden retriever. She noticed that her dog could smell scents and detect nuances on the trails that she could not. So, in efforts to be aware of the nature around her, she practiced listening with her ears since her sense of smell was not as potent for her.

“You can hear all kinds of things in the woods that you could never see,” she said.

Brown explained that in this moment of listening, Psalm 46:10 came to her mind which reads, “Be still, and know that I am God.” She mentioned that in the Biblical context, this was a command during a time of war and unrest—a command to be still and know, she said.

“The world has been full of so much hate and difficulty and loss,” she said. “It’s very difficult to surrender to just being there—to just being aware.” Brown encourages others to not just pass nature by, but to stop, take notice and learn the “literacy of the forest.”

Awareness of Earth’s creatures also comes with the responsibility of a call to action. Brown hopes her poems help people to care more about preserving animal life.

“They’re dying,” she said, referring to birds. “Even our insects are dying.”

Instead of passively hoping animals survive, she wants people to actively do all they can to help wildlife thrive.

“I do believe that hope has very little to do with how you feel. Hope is about what you do.”